Our Better Angels: The Effects of Implicit Assumptions on the Integrity and Mentoring Behavior of Top Executives.

In the Human Side of Enterprise (1960), Douglas McGregor made the provocative assertion that “behind every managerial decision or action are assumptions about human nature” (p. 33). McGregor’s theory has been cited by both scholars and practitioners as among the “most influential” and “most useful” ideas in management (Bedeian & Wren, 2001; Miner, 2003), and while his theory continues to be referenced, it has received limited empirical scrutiny (Miner, 2003). This study seeks to address this gap.

This study will examine how the integrity and mentoring behaviors of executives are shaped by their implicit assumptions. Integrity is the bedrock for sustainable business performance (Lennick & Kiel, 2007). It is also an important component of a leader’s character and moral intelligence. Lennick & Kiel (2007) describe the importance of integrity and moral intelligence as a capacity for effective leadership. This purpose of this study resonates with the mission of the Think2Perform Research Institute in that it examines the psychological foundations of integrity and leadership development – elements that are critical to moral intelligence and purposeful leadership.

In addition, we focus on the mentoring behaviors of upper echelon leaders—a population with significant influence in organizations (Hambrick & Mason, 1984) yet understudied in mentoring research. Taking a social cognitive approach, we consider antecedents of supervisory career mentoring – mentoring that leaders provide to their direct reports (Scandura & Schriesheim, 1994). Specifically, we examine implicit assumptions about followers’ characteristics, known as theory X/Y beliefs (McGregor, 1960).

MANAGERIAL ASSUMPTIONS, INTEGRITY, AND MENTORING

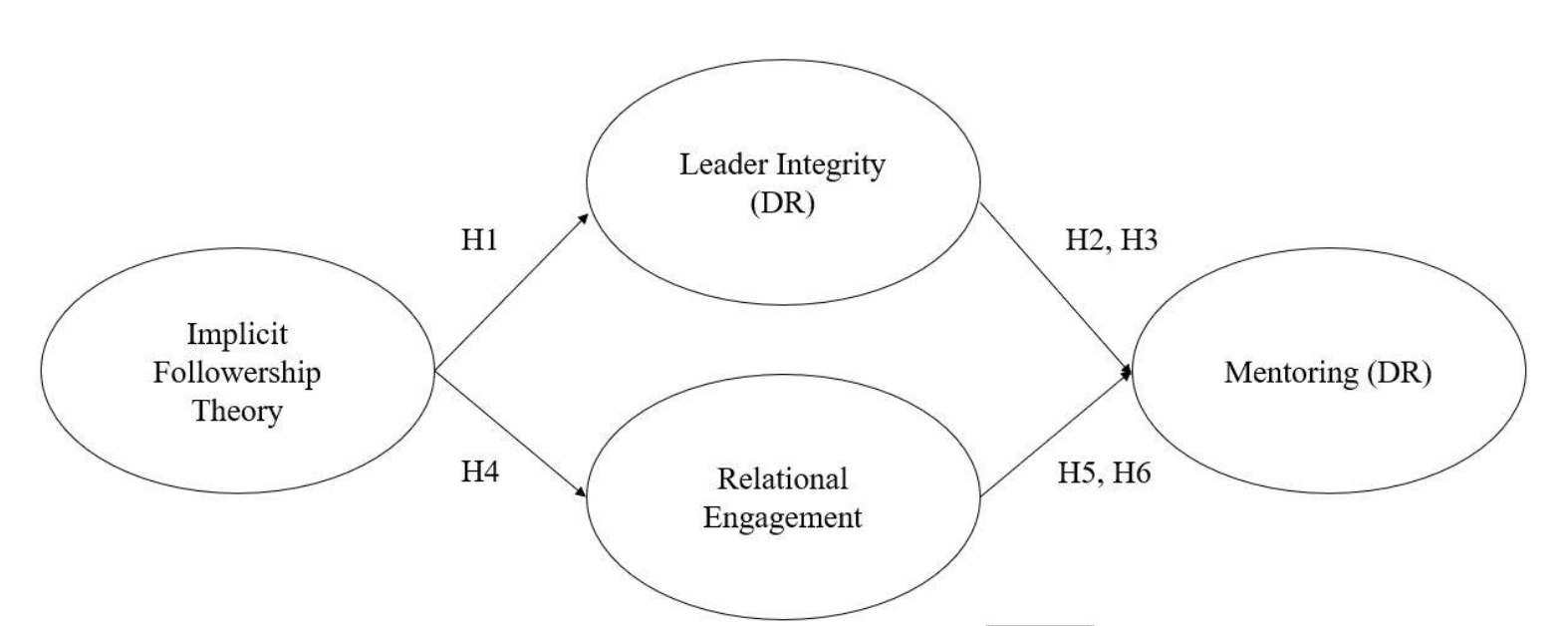

McGregor described two fundamentally different types of managerial assumptions about human nature and motivation – what he describes as Theory X and Theory Y. Theory X is a set of managerial assumptions based on the premise that people are not intrinsically motivated to work and need to be directed by management. Theory Y, on the other hand, is a belief that people are interested in assuming responsibility and are intrinsically motivated. Taking a social cognitive approach, we consider how an executive’s implicit followership theory (Theory X and Y) is related to their effectiveness as mentors. In addition, we propose two mediators to this relationship – behavioral integrity and relational engagement. The figure below provides a summary of our hypothesized model:

METHODS AND EARLY FINDINGS

We have completed data collection with a multisource sample of top executives (n=331) and their direct reports (n=1517). The executives were participants in a senior leadership program at a global executive education organization based in the United States. Participants included top executives with more than 15 years of management experience, leadership responsibility for 500 or more people, and decision-making authority as members of the senior management teams. Data were collected over 16 months, involving all participants of the program.

Results support the proposed social cognitive theory of mentoring, where optimistic implicit followership theories of executives are positively related to relational engagement and leader integrity, which in turn are positively related to mentoring effectiveness as rated by the executive’s direct reports. In other words, there are significant links between how leaders think, feel, and behave as mentors to their followers.

TIMELINE

July 2020: Presentation ready for Think2Perform board and community

Practical Implications

The findings of this study offer several practical implications for leaders and organizations. At a broad level, the results can help leaders and organizations attend to implicit assumptions about followership instead of focusing only on explicit leadership behaviors. More specifically, the findings of the study can be used to develop the following applications:

- An assessment to help leaders understand their implicit assumptions

- A coaching model focused on implicit assumptions as a driver of leadership behavior

- A team intervention to surface team-level assumptions

- An organization development intervention to shift implicit assumptions

Overall, the findings of this study suggest that leaders need to question their implicit theories of followership and how it influences their feelings and behavior toward others. Recognition of implicit theories, integrity, and relational engagement, in oneself and others, provides useful information for the leaders. Multisource assessments of implicit theories, integrity, and engagement could be integrated into leadership coaching and training to facilitate this.

For more information, please contact Jeffrey Yip at j_yip@sfu.ca

REFERENCES

Hambrick, D. C., & Mason, P. A. (1984). Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Academy of Management Review, 9, 193-206.

Lennick, D., & Kiel, F. (2007). Moral intelligence: Enhancing business performance and leadership success. Pearson Prentice Hall.

McGregor, D. (1960). The human side of enterprise. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Scandura, T. A., & Schriesheim, C. A. (1994). Leader-member exchange and supervisory career mentoring as complementary constructs in leadership research. Academy of Management Journal, 37, 1588–1602.